By Dr. Selwyn R. Cudjoe

March 21, 2008

On February 20, the University of the West Indies inaugurated its Year of Sir Arthur Lewis as part of its celebration of the three Nobel Laureates from the English-speaking Caribbean.

On February 20, the University of the West Indies inaugurated its Year of Sir Arthur Lewis as part of its celebration of the three Nobel Laureates from the English-speaking Caribbean.

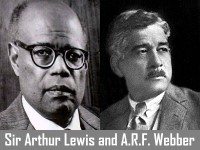

During the year much will be said about Lewis’s achievements. Little would be said about his contribution to the formation of Caribbean intellectual thought and the pioneering work that ARF Webber did in theorising about Caribbean economics. It is a position I outline in Caribbean Visionary: ARF Webber and the Making of the Guyanese Nation that is being published by the University Press.

There can be no doubt that Lewis was as an outstanding theorist of Caribbean economic thought. Together with Webber and CLR James, he was part of a magnificent triumvirate whose works sowed the seeds for an indigenous intellectual tradition and helped to advance a vision of what a liberated Caribbean person ought to be.

Although these societies took a long time before they gained their independence, the work of these three freedom fighters played an important part in setting the intellectual terrain in which subsequent generations planted their academic seeds.

Webber was a Tobagonian who made his name in Guyana’s politics. He was one of the most important Caribbean intellectuals of the 20th century although he fell out of our nation’s history.

“Why I am an Economic Heretic,” an article that Webber wrote in 1930, anticipated the central argument that Lord Maynard Keynes made in this seminal work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in 1936. Chip Case, an economist at Wellesley College, argues that Webber “either anticipated Keynes or he was one of the first practitioners.”

Webber was a legislator in the Guyanese Legislative Council from 1921 to 1932. As a result, he was deliberating on economic issues when Lewis had not given a thought to economic theorising. Lewis says that when he went to London School of Economics (LSC) in 1933 he had “no idea what economics was.”

In 1936 Lewis wrote “The Evolution of the Peasantry in the West Indies,” in which he argued that “the sugar depression has called in question the foundation of West Indian society.”

He believed that the salvation of the West Indies lay in the transformation of the economy from plantation to peasant production.

When Lewis wrote this essay there existed no formal economic theorising in the Caribbean. Eric St Cyr, a local economist, says there were two strands of economic thinking at the time: “a mixture of mercantilist thought and 19th century liberalism, with a smattering of Keynesianism later in the day.”

He notes that “Lewis’s unlimited supplies model is clearly the first attempt at theory construction for a specific West Indian economic problem.”

Webber, like Lewis, was a member of the “transitional” generation who was concerned about the devastating effect the 1929 economic depression had on Caribbean society.

Webber could only see dimly what Keynes, a professional economist, saw more clearly and which took Lewis a longer time to see. Thirty years into his work, Lewis was more explicit about the activist role of government in economic development.

In 1983, in his presidential address to the American Economic Association, he argued for “a theory of government” that changed from “viewing government as autonomous and an exogenous factor in any development analysis to making government endogenous.”

Webber and Lewis agreed on two things. Webber saw Guyana’s problems as being a subset of a larger international problem whereas Lewis “never considered the LDCs in isolation but always in the context of a world economy as a single interdependent system.” That was his major strength as an economist.

Lewis also saw the strengthening of peasant production and the transformation of the political system as two ways to solve the chronic economic situation that faced the working people of the Caribbean.

He suggested that “if the state ceases to be dominated by the plantocracy, if, for instance, a change in the franchise brings political power within the range of labourers and peasants, the prospects of the peasantry will become brighter. Whether or not such a change is probable within the near future, we cannot say.”

Lewis and Webber were close to the Fabian society in London. The Fabian Society was responsible for Lewis’s publication of Labour in the West Indies that was subtitled “The Birth of a Workers’ Movement.” As early as 1938, Lewis realised that the political salvation of the Caribbean lay in the hands of those who controlled the state.

Both Webber and Lewis believed that the adaptation of socialism offered one way out of Caribbean dependency although each man strove to achieve this end through a form or parliamentarianism.

Each man believed that the working people should control their labour power and emphasised the important role that economics played in the formation and subsequent transformation of Caribbean society.

Although Webber died before Lewis commenced his economic studies, the former was an important intellectual link to the latter.

The country ought to know more about Webber even as we celebrate Lewis’s contribution to Caribbean and international economic thought. We need to treasure our geniuses and honour their memories.

http://www.trinicenter.com/Cudjoe/2008/2103.htm